Ed Wilkins in Myanmar- Week 35

So herewith the first of another super-late series of epistles charting a smattering of my fondest moments, both significant and trivial, from the archival footage of the 5 weeks of blogs that have somehow got misplaced lest they be forgotten in the deep recesses of my rapidly involuting grey cells. And as I start this particularly late collection of ‘letters from Myanmar’, I ponder the fact that, as with other medics, nurses, and pharmacist volunteers who have for a variety of individual and partner reasons ended up in this country with its three seasons of hot, dead hot (literally), and swim-suit wet, and who I have seen with a heavy heart chart their paths back home expectantly preparing themselves for the next stage of their careers. I too will be following in their collective footsteps but luckily not to work but to my wonderful and unsurpassably patient and incomparable loyal wife and family, and of course the continuing retirement process.

Yes, in one of those bitter-sweet moments, it will be my time to say the fond fare-the-wells this December after nigh on two years in this country and a life that on reflection has rewarded me in more ways than I can ever have imagined when I embarked to Myanmar after the hard sweat of twenty-seven years as a consultant with my beloved NHS and Manchester. Yes, in my two years frequently interrupted by planned trips home to family and friends, I have come away having had experiences that will provide my dementing brain many anecdotes to recount to grandchildren, and with new friendships that will last forever. So, at the very beginning of this next box-series of Netflix highlights, please indulge me by allowing a few everyday pictures of Yangon life: the flat essentials that always travel with me (tea, marmite, marmalade, and my family on a good mug) (picture 1), the small monastery next door where a metal tube is whacked chiming the hour all through the night which wakes even the most hardy of comatose residents (picture 2) including me, especially when partnered with the dawn chorus of cockerels who live outside my bedroom window; my long-suffering and oft-quoted Dutch flatmate and me (picture 3); and my go-to coffee house where I can get a flat-white and be reminded of home (and pen my blogs) (picture 4).

This also has the added and very attractive advantage of delaying some of the more relevant and interesting revelations about clinic Oscar-highs and wooden-spoon lows till the next blog – that is if any wavering volunteer potentially considering stepping off the NHS gangplank is awaiting something clinical to whet his or her appetite to book that airplane ticket.

But, again diverging significantly from the whole purpose of this blog and continuing the theme about flats, describing my humble abode has reminded me of my fascinating discussion with the director of Myanmar’s Emergency Centre for Transboundary Animal Diseases (snappy title) about pig zoonoses (not everyone’s cup of tea). Pig-bugs is an area of interest for him and if they can be passed from the pig to human, then of interest to me too. Consuming pork is the usual mode of transmission so that anywhere where you put pig-eaters and pigs together is, I think, perfect ground for an illness characterised by sudden and nasty inflammation of the liver (hepatitis E) to be an endemic problem for pigs and man alike. And boy do they like their pork here! It is one of the two staple meats (chicken being the other), with pork-stick (skewered offal basically – anything from colon to placenta) being sold on every street corner from dusk to midnight (picture 5) which is then cooked flambé-style there and then at maybe less than Michelin standards.

Anyway, this party-clearing chat digresses from the true story, which has a moral. Having suffered an electrical fault with an appliance which unfortunately led to a fire in one room of his flat which was extinguished before the fire brigade even arrived, this eminent long-serving director ended up in court, had his passport confiscated, and was asked to leave the country and from my reading this relates to the ‘Burma Foreigner’s Act of 1864’; definite bed-time Kindle reading for the insomniac. Luckily, with contacts in high places he has had his criminal record expunged and can continue his valuable work in this country and most importantly return of his passport (and we can continue our fascinating chats about pig-bugs). Moral of the story? Have dual citizenship and a spare passport or bring in plenty of duty free to cheer yourself up.

Going back to something a tad more relevant to those of you working within the broad health care fraternity. Having returned from the UK after a prolonged sojourn to celebrate my 65th and the receipt of pension and bus-pass (and escape the monsoon rains) as well as revitalise with good wine and calorie-laden food enhanced siestas, it was as exciting as it was on my first day to arrive back in the clinic again, tread those bamboo floors and reunite with the staff beavering away at their increasing workload. Maybe a touch of rose-tinted specs there given the winter heat (33oC), but despite the reminder of the seemingly insurmountable level of clinical disease, it is heart-warming to see the determined enthusiasm that, like all those before them, the current bunch of volunteers (two nurses and one doctor) are applying to their work. With youthful vigour and no short supply of noble altruism, their single aim is to use their skillsets to improve the quality of patient care. I’ve often mentioned the need to be prepared for obstacles that set plans back, but with the current bunch there is an impressive collective doggedness and courage to overcome this and not get too disheartened. And that’s the advantage of being one of many as opposed to being on your todd. They return to the UK around Xmas/New Year to a period of readjustment to life in the NHS and its restrictions, mandatory training, appraisals, enforced teaching sessions, and governance demands: much of it vital to quality care but far removed from the clinic work they’ve been doing here and therefore a bit of a reverse culture shock.

But in the clinic itself, the complaints range from the trivial respiratory tract virus infections to the challenging neurological case (pardon the jargon non-medics, but complete unilateral ptosis, no ophthalmoplegia, and ipsilateral ataxia) and the mother and 3y old child with HIV, neither on HIV treatment – the mum is non-compliant which does not bode well for the child – the little’un is unaware of the problems it faces ahead, instead intent on obtaining a quick bit of nourishment (picture 6). There has been a significant move to improve the recording and care for the non-communicable diseases, especially diabetes and hypertension.

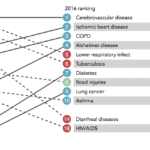

Unbelievable though it may seem, but TB and HIV no longer take Champions League positions in the premier league in mortality and morbidity; these unenviable prizes go to our old Western friend’s, the likes of cardiovascular disease and diabetes (picture 7). Now, screening protocols, rubber-stamp templates for each ‘passport’ (the hand-held case notes), and nurse-led investigations, all take place before the patient sees the doctor and this process is being rolled out by ever-enthusiastic UK nurses and doctors who are giving their metaphorical heart and soul to get this, and numerous other critical projects, absorbed into clinical practice. Married together with a medical proforma to be rolled out for diabetes and hypertension, this moves the clinic management forward by an enormous leap – the one to be mentioned in dispatches with medal and bar deserves a photo for her Olympian efforts (picture 8).

Oh, and in case you’re wondering what the neurology case has, I don’t know but I suspect it is a midbrain lesion and given he has underlying but well controlled HIV with a pretty good immune system, TB seems the most likely culprit but still doesn’t fit the bill entirely. Hence a referral to a neurologist and onwards to scanning is a definite and urgent next step.

It seems that before you realise, you’re having to wind up the blog because you’re at the bottom of your second page. But I make a pledge that the next blog will be stuffed full of more relevant material. For now, I’ll finish with a few titbits from the clinics. For those in the know, PEP (or more correctly Post Exposure Prophylaxis) is an effective way of preventing HIV occurring should a health care worker be unfortunate enough to suffer a needle-stick injury and consists of a whole load of pills which you take for a month and that should, if you can stomach them, hopefully do the job. An alternative was spotted in the clinic the other day (Picture 9) which, despite looking maybe more palatable, won’t achieve the desired purpose alas. The impressive tattoo (picture 10) of a chap’s kiddywinks birthdays indicates that he either adores his kids or is just losing it slightly like me and needs reminding of their birthdays: unfortunately, it may be the source of his hepatitis! Sorry Jen, Pete, Fred, and Flo: not for me I’m afraid (if you are bothering to read this that is!). Till next time then!

Ed